Which Of The Following Is True About The Use Of Makeup In Ancient Egypt?

How ancient Egypt shaped our thought of beauty

(Image credit:

Two Temple Place/Macclesfield Museum

)

Pop culture is steeped in images of smoky-eyed pharaohs and their queens. Were the ancient Egyptians insufferably vain – or are we simply projecting our own values onto them? Alastair Sooke investigates.

W

Walking around Beyond Beauty, the new exhibition organised by charitable foundation the Bulldog Trust in the neo-Gothic mansion of 2 Temple Place in central London, you would be forgiven for thinking that the ancient Egyptians were insufferably vain.

Many of the 350 exhibits, drawn from the overlooked collections of Britain's regional museums, consist of what nosotros would call beauty products, of i sort or another.

In that location are dinky combs and handheld mirrors made of copper alloy or, more rarely, silver. At that place are siltstone palettes, carved to resemble animals, which were used for grinding minerals such as green malachite and kohl for eye makeup.

There are also pale calcite jars and vessels of assorted sizes, in which makeup, as well as unguents and perfumes, could be stored. Then in that location is a scrap of human hair that suggests the ancient Egyptians commonly wore hair extensions and wigs.

This copper blend mirror from the 2d Millennium BC has a handle made out of stone that looks like a cavalcade of papyrus (Credit: Courtesy Two Temple Place/Macclesfield Museum)

And, of form, at that place are lots of hitting examples of Egyptian jewellery, including a string of beads, decorated with carnelian pendants in the shape of poppy heads, found in the grave of a small kid wrapped in matting.

In brusque, aboriginal Egyptians of both sexes plain went to great lengths to touch up their appearance.

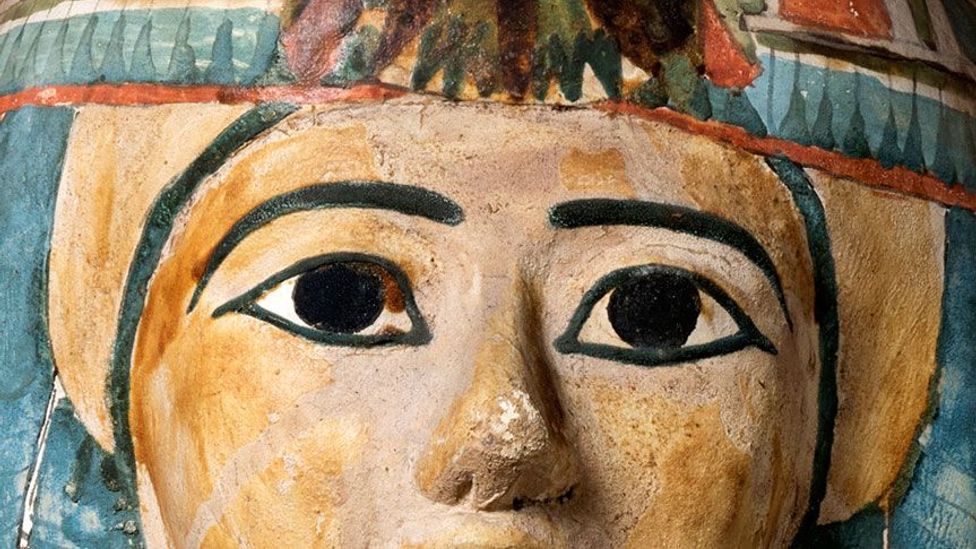

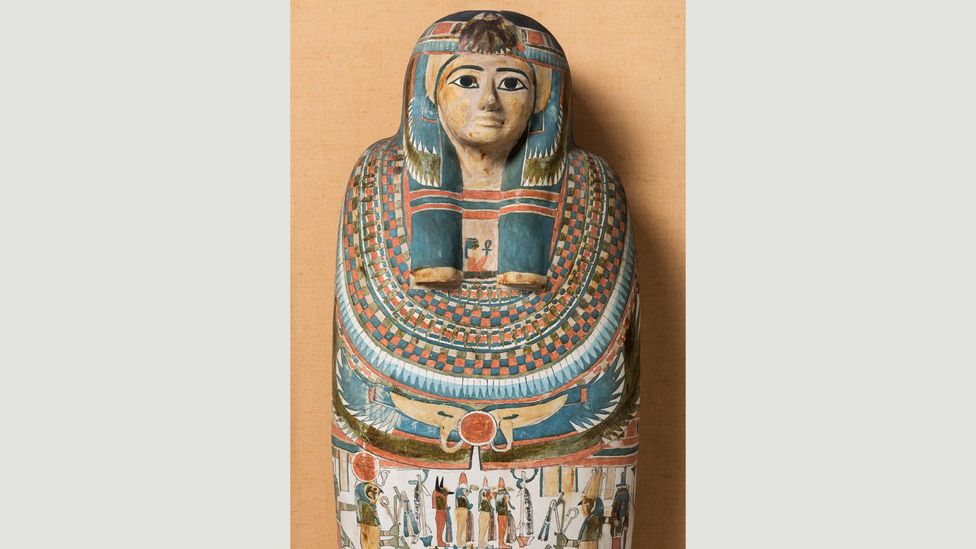

Moreover, this was just equally true in death as it was in life: witness the smoothen, serene faces, with regular features and prominent optics emphasised by dramatic black outlines, typically painted onto cartonnage mummy masks and wooden coffins.

Yet, for modern archaeologists, the ubiquity of dazzler products in ancient Egypt offers a conundrum.

On the one hand, it is possible that aboriginal Egyptians were besotted with superficial appearance, much as we are today. Indeed, maybe they even set the template for how nosotros still perceive beauty.

But, on the other, there is a take a chance that we could project our own egotistic values onto a fundamentally different civilisation. Is it possible that the significance of cosmetic artefacts in ancient Egypt went beyond the frivolous desire only to wait bonny?

Sensibly sexy

This is what many archaeologists now believe. Take the mutual use of kohl eye makeup in ancient Egypt – the inspiration for smoky eye makeup today. Recent scientific research suggests that the toxic, pb-based mineral that formed its base would accept had anti-bacterial properties when mixed with wet from the optics.

Elaborate sarcophagi depict faces with heavy centre-liner – only make-up for the ancient Egyptians was functional too as aesthetic (Credit: Two Temple Place/Macclesfield Museum)

In addition, the heavy application of kohl around the eyes would have helped to reduce glare from the dominicus. In other words, in that location were simple, practical reasons why both men and women in ancient Egypt wished to wear eye makeup.

Information technology's the same with other ancient Egyptian 'beauty products'. Wigs helped to reduce the risk of lice. Jewellery had powerful symbolic and religious significance.

A fired dirt female figure, depicting an erotic dancer, excavated at Abydos in Upper Egypt and now in the exhibition at Two Temple Place, is embellished with indentations that were meant to stand for tattoos. Of course, in ancient Egypt, tattoos probably had a decorative purpose.

But they may accept had a protective function too. There is evidence that, during the New Kingdom, dancing girls and prostitutes used to tattoo their thighs with images of the dwarf deity Bes, who warded off evil, as a precaution against venereal disease.

"The more I attempt to sympathise what the Egyptians themselves understood as 'beautiful'", says Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley, "the more disruptive information technology becomes, because everything seems to accept a double purpose. When it comes to ancient Egypt, I don't know if 'dazzler' is the right give-and-take to apply."

These cosmetic pots contained kohl, which the aboriginal Egyptians applied similar eye-liner, perhaps to screen out the dominicus (Credit: Two Temple Place/Ipswich Museum)

To complicate matters further, there are heart-catching exceptions to the general rule whereby aristocracy ancient Egyptians presented themselves in a stereotypically 'beautiful' way.

Consider the official portraiture of the Middle Kingdom pharaoh Senwosret 3. Although his naked torso is athletic and youthful – idealised, in line with before royal portraits – his face up is careworn and cracked with furrows. Moreover his ears, to modern viewers, appear comically large – hardly an attribute, y'all would retrieve, of male beauty.

Notwithstanding, in aboriginal Egypt, the effect wouldn't have been funny. "In the Old Kingdom, kings were god-kings," explains Tyldesley, who is a senior lecturer at the University of Manchester. "Simply by the Middle Kingdom, kings [such as Senwosret] recognised that things could crumble and become wrong, which is why they look a fleck worried."

"The big ears are telling us that this king volition heed to the people," she adds. "It would be wrong to have his portrait literally and say he looked like this."

Queen of the Nile

Why, and so, do we go along to associate ancient Arab republic of egypt with glamour and dazzler? "We however find ancient Egyptian civilisation very seductive," agrees Tyldesley, who believes that this is due to the afterlives of 2 famous Egyptian queens: Cleopatra and Nefertiti.

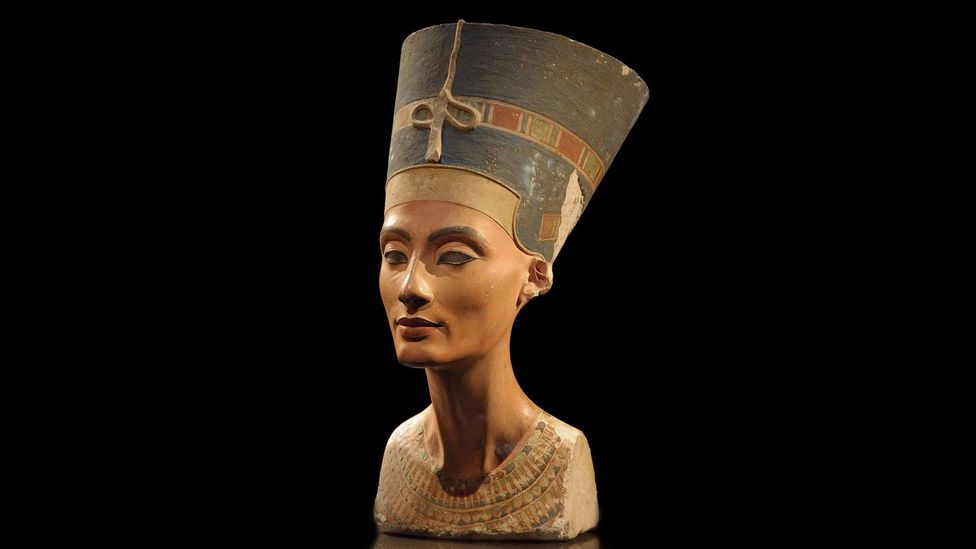

Always since antiquity, following the Roman conquest of Egypt, Cleopatra has been known as a paragon of beauty. Meanwhile the discovery, in 1912, of the famous painted bust of Nefertiti, now in Berlin's Egyptian Museum, turned a little-known married woman of the pharaoh Akhenaten into a pivot-up of the ancient world.

Withal, says Tyldesley, who has written a biography of Cleopatra and is researching a book on Nefertiti, there is irony to the fact that these two Egyptian queens now resonate as sex activity symbols.

For i thing, explains Tyldesley, "Cleopatra has given u.s. the thought that aboriginal Egyptian women were all cute, merely we don't actually know what she looked like."

In her coinage, Tyldesley says, "Cleopatra had a big nose, a protruding mentum, and wrinkles – not what virtually people would call beautiful. You could fence that she appeared on her coins like that on purpose, because she wanted to expect stern, and not particularly feminine. But even Plutarch, who never met her either, said that her beauty was in her vivacity and her vocalism, and not in her appearance. Yet nosotros take decided that she was beautiful and that she has to await like Elizabeth Taylor. I think that the idea of Cleopatra, rather than Cleopatra herself, has influenced us."

The notion of aboriginal Egyptians every bit glamorous comes largely from Cleopatra, whose wiles ensnared Caesar – Elizabeth Taylor did not discredit that idea (Credit: 20th Century Fox)

As for Nefertiti, Tyldesley points out that her bust is not typical of ancient Egyptian art: "It's an unusual statue in that it's got all the plaster on and it'southward colourful – a lot of the artwork we have is more stereotyped and less personal-looking than that."

Moreover, the moment when the bust was unveiled in Berlin – in 1923 – was crucial to its reception. 'Egyptomania' was in the air, following the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun the previous yr, and Nefertiti'south angular, geometric appearance chimed with fashionable taste. "She'due south very modern-looking, very Fine art Deco," says Tyldesley. "So everybody seemed to like her. It'due south hard to observe anybody who didn't think that Nefertiti was cute."

When this bust of Nefertiti was discovered in 1912, the queen instantly became a sex symbol of the ancient earth (Credit: Philip Pikart/Wikipedia/CC BY-SA iii.0)

During the '20s, the bust of Nefertiti besides benefited from the ability of the mass media to plough her into a star. "A hundred years earlier, without newspapers or the movie theatre, that wouldn't have happened," says Tyldesley. "She would take gone into a museum and nobody would have made the fuss they did."

She pauses. "I wonder whether the fact that Nefertiti was put on display in Berlin as a major find actually influenced what we saw. After all, beauty, every bit nosotros know, is in the middle of the beholder."

Alastair Sooke is Art Critic of The Daily Telegraph

If y'all would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Civilisation, caput over to our Facebook folio or bulletin us on Twitter

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160204-how-ancient-egypt-shaped-our-idea-of-beauty

Posted by: woodtimstrance1982.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Of The Following Is True About The Use Of Makeup In Ancient Egypt?"

Post a Comment